Stanford Researchers Discover Immune System’s Rules of Engagement

By finding surprising similarities in the way immune system defenders bind to disease-causing invaders, a new study may help scientists develop new treatments.

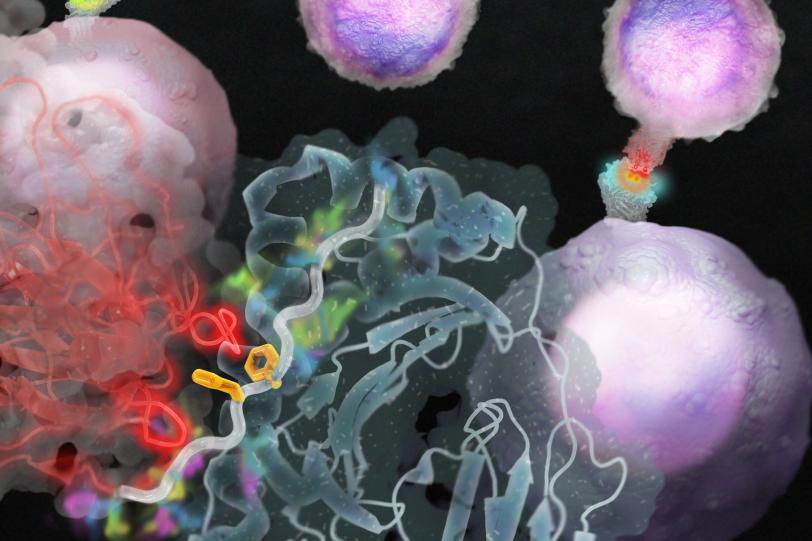

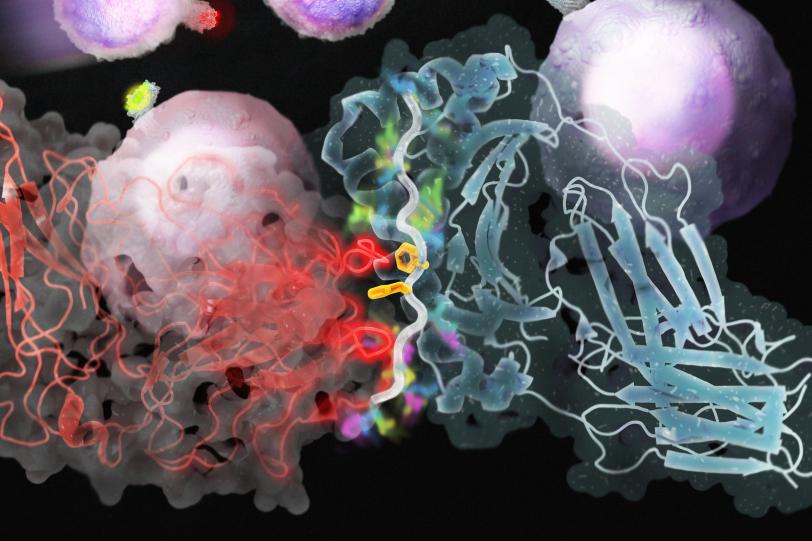

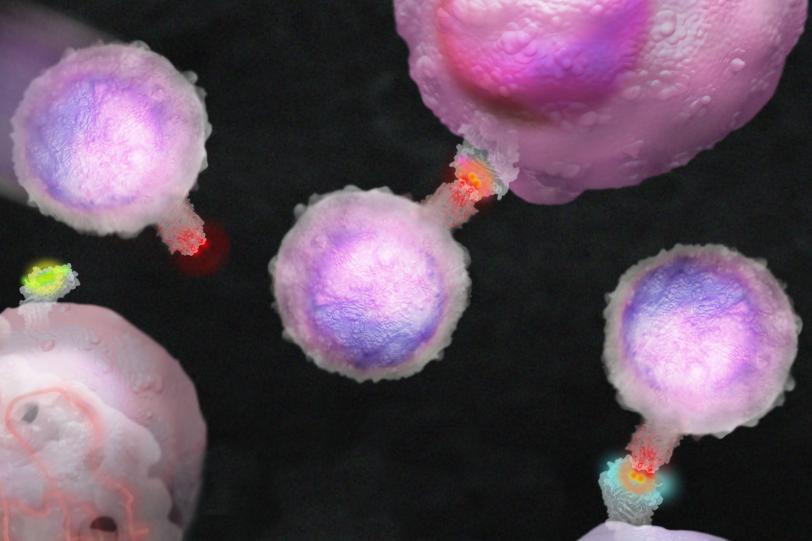

A study led by researchers at Stanford's School of Medicine reveals how T cells, the immune system's foot soldiers, respond to an enormous number of potential health threats.

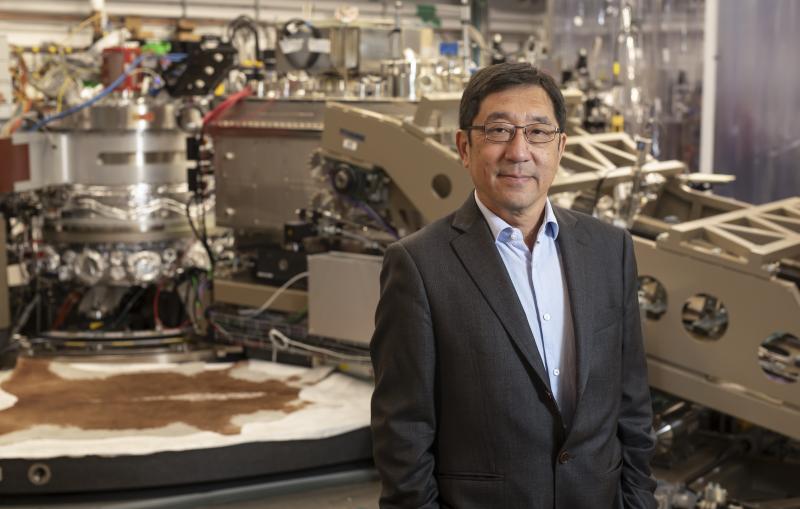

X-ray studies at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, combined with Stanford biological studies and computational analysis, revealed remarkable similarities in the structure of binding sites, which allow a given T cell to recognize many different invaders that provoke an immune response.

The research demonstrates a faster, more reliable way to identify large numbers of antigens, the targets of the immune response, which could speed the discovery of disease treatments. It also may lead to a better understanding of what T cells recognize when fighting cancers and why they are triggered to attack healthy cells in autoimmune diseases such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

"Until now, it often has been a real mystery which antigens T cells are recognizing; there are whole classes of disease where we don't have this information," said Michael Birnbaum, a graduate student who led the research at the School of Medicine in the laboratory of K. Christopher Garcia, the study's senior author and a professor of molecular and cellular physiology and of structural biology.

"Now it's far more feasible to take a T cell that is important in a disease or autoimmune disorder and figure out what antigens it will respond to," Birnbaum said.

T cells are triggered into action by protein fragments, called peptides, displayed on a cell's surface. In the case of an infected cell, peptide antigens from a pathogen can trigger a T cell to kill the infected cell. The research provides a sort of rulebook that can be used with high success to track down antigens likely to activate a given T cell, easing a bottleneck that has constrained such studies.

Combination Approach

In the study, researchers exposed a handful of mouse and human T-cell receptors to hundreds of millions of peptides, and found hundreds of peptides that bound to each type. Then they compiled and compared the detailed sequence – the order of the chemical building blocks – of the peptides that bound to each T-cell receptor.

From that sample set, which represents just a tiny fraction of all peptides, a detailed computational analysis identified other likely binding matches. Researchers compared the 3-D structures of T cells and their unique receptors bound to different peptides at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Research Lightsource (SSRL).

"The X-ray work at SSRL was a key breakthrough in the study," Birnbaum said. "Very different peptides aligned almost perfectly with remarkably similar binding sites. It took us a while to figure out this structural similarity was a common feature, not an oddity – that a vast number of unique peptides could be recognized in the same way."

Researchers also checked the sequencing of the peptides that were known to bind with a given T cell and found striking similarities there, too.

"T-cell receptors are 'cross-reactive,' but in fairly limited ways. Like a multilingual person who can speak Spanish and French but can't understand Japanese, a receptor can engage with a broad set of peptides related to one another," Birnbaum said.

Impact on Biomedical Science

Finding out whether a given peptide activates a specific T-cell receptor has been a historically piecemeal process with a 20 to 30 percent success rate, involving burdensome hit-and-miss studies of biological samples. "This latest research provides a framework that can improve the success rate to as high as 90 percent," Birnbaum said.

"This is an important illustration of how SSRL's X-ray-imaging capabilities allow researchers to get detailed structural information on technically very challenging systems," said Britt Hedman, professor of photon science and science director at SSRL. "To understand the factors behind T-cell-receptor binding to peptides will have major impact on biomedical developments, including vaccine design and immunotherapy."

Additional contributors included the laboratories of Mark Davis, the Burt and Marion Avery Family Professor at Stanford School of Medicine, and Kai Wucherpfennig at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. SSRL is a scientific user facility supported by DOE's Office of Science.

Citation: M.E. Birnbaum et al., Cell 22 May 2014 (10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.047)

This article originaly appeared on the Stanford News website.

Media Contacts:

K. Chris Garcia, Department of Molecular & Cellular Physiology, Stanford School of Medicine: (650) 498-7111, kcgarcia@stanford.edu

Dan Stober, Stanford News Service: (650) 721-6965, dstober@stanford.edu

Manuel Gnida, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, 415-308-7832

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information, visit ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.